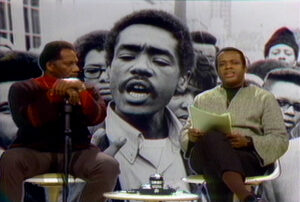

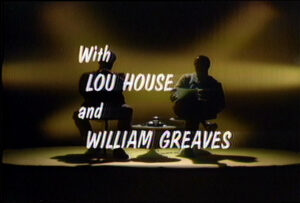

Black Journal (1968-1970) is a landmark in American broadcast history as the first nationally-televised, regularly-scheduled African-American public affairs program, providing a unique perspective on the Civil Rights period. Lou House (who later changed his name to Walli Sadiq) and William Greaves were the co-hosts. Alvin H. Perlmutter was the executive producer for the first three shows; in September 1968, Greaves became the executive producer for Black Journal 4 and continued in that position for the rest of the shows, while also continuing as co-host.

The series debuted in June 1968 and was broadcast during prime time by many public television stations. Between June 1968 and April 1970, twenty-three episodes were produced, and in 1970, Black Journal won an Emmy for programming excellence in public affairs.

Black Journal reported on the impact of the recent assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., the government’s secret campaign against the Black Panther Party, the election of Richard Nixon as President, liberation movements in Mozambique and South Africa, as well as school bussing, housing integration, and labor struggles from Mississippi to New York. It interviewed Black leaders from across the political spectrum: Julian Bond, Huey P. Newton, Roy Innis, Kwame Turé (Stokely Carmichael), Hon. Elijah Mohammad, Betty Shabazz, Rev. Jesse Jackson, and Coretta Scott King. They and many others debate future directions for the Black Freedom Struggle – electoral politics, Black Nationalism, Pan-Africanism, self-determination in Black communities, Black entrepreneurship.

Black Journal also featured prominent African American artists, including James Brown, Ed Bullins, Nina Simone, Melvin Van Peebles, Roberta Flack, John Lee Hooker, and Nikki Giovanni, showing how the ferment in Black American life was reflected in the country’s cultural life.

To see a detailed description of the contents of all 23 programs from 1968-1970, courtesy of California Newsreel, click here. For the link to view all episodes for free, go to the Purchase/Stream page.

Greaves on Black Journal:

“Periodically there was a little anxiety at NET, for instance when we decided to do a show on the Black Muslims, or Paul Robeson, or Malcolm X; but quite interestingly we had a great deal of freedom on that show. That is to say I was not bugged by the management of NET for several good reasons. First, they were basically people of good will. But more importantly, perhaps, was the fact that we had developed a lot of political clout. I had purposely cultivated the black press, so they were very much behind us; I cultivated the people in the Congressional Black Caucus.

And, of course, there were all these riots and demonstrations going on, so they knew if they in a sense touched us, they might get burned. I’m overdramatizing this, but the situation in the sixties was so volatile and tense that it would have made no sense whatsoever for them to have this heavy hand on a show that had been put together specifically for the purposes of expressing the concerns of the black community. That was the point made by the Kerner Commission on Civil Disorder and the Carnegie Endowment. They would have been violating the mandate of the show.”

–Excerpt from “William Greaves, Documentary Film-making, and the African-American Experience” by Adam Knee and Charles Musser in Film Quarterly (1992). The full text can be found in “William Greaves: Filmmaking as Mission” (Columbia University Press, 2021).

“I remember seeing the very first edition of Black Journal and realizing that Bill Greaves was ahead of the times – so much so that his pioneering work then helped shape the times. He showed us that both the past and present — history and journalism – were essential to a full account of American life.”

–Bill Moyers, Journalist and political commentator

“An archive of art and realism that remains vital to this day. I was a huge fan of the riveting series Black Journal, which challenged the generation living through the convulsive years of the late sixties to wrestle with and define for ourselves the true meaning of access, mobility, and power. Anyone seeking a more enlightened ‘conversation on race’ today should go back to the brilliant series and, working through it, understand the foundation upon which race relations in America today is constructed.”

–Henry Louis Gates, Harvard University

“Black Journal was the pacesetter. Public television, at its best, challenges us to reexamine our assumptions and expand our inventory of ideas. Black Journal did that and more, introducing Americans to each other. We owe this groundbreaking show a deep debt.”

–Tavis Smiley, The Tavis Smiley Show

“The series illuminated a crucial period in the African-American Freedom Struggle with programs featuring discussions that tried to respond to Martin Luther King’s final challenging and enduring question: Where do we go from here?”

–Clayborne Carson, Stanford University

“Anyone interested in American media and politics should make sure to study the wide-ranging work.”

–John L. Jackson, Jr., University of Pennsylvania

The Revolution Was Televised: On the Legacy of Black Journal

It started with an all-white background. From the side of the frame emerged a black man, dressed in frumpy cream overalls and a painter’s cap. In his hand was a paint roller, and from the opposite side of the frame he began painting the screen methodically, moving from top to bottom, left to right, obscuring the entire area. By the end, the whole screen was black. With no words and a simple visual metaphor, it was clear that what you were about to see was not your typical television program.

This was the bold introduction to Black Journal, which aired its first episode on PBS on June 12, 1968, just over four months after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Introduced by National Education Television, with funds supplied by the Ford Foundation, the show was co-created by Al Perlmutter, a white staff producer at NET who had recently arrived from NBC. In the wake of King’s death and the publication of the Kerner Report, which concluded that the country was “moving toward two societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal,” Perlmutter was brought in to originally make a documentary about the riots spreading across the United States that summer. But according to media scholar Devorah Heitner in her book Black Power TV, he was able to convince executives to take the money planned for the documentary and move it into producing what would soon become Black Journal.

But the show didn’t materialize out of thin air. The existence of Black Journal was part of a wave of local programming across the country that worked toward engaging black audiences by presenting stories told from their perspective. (In New York alone you had programs such as Inside Bedford-Stuyvesant and Like It Is, both equally worthy of advanced consideration.) But Black Journal was the biggest, with a reported initial budget of $500,000 per season, and the first to be syndicated around the country. With a wider reach, its mission was considerably broader. As Lou House (who later changed his name to Wali Sadiq) announced at the beginning of the premiere episode: “It is our aim in the next hour and in the coming months to report and review the events, the dreams, the dilemmas of Black America and Black Americans.’’

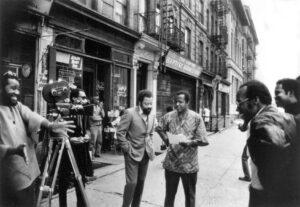

“It was quite a remarkable period because, you have to remember, there was not another show like that on national television,” Charles Hobson, who worked on the first and second season of· Black Journal said in an interview. “These were smart, militant, educated black men and women, telling stories from the black experience.”

Only recently have the filmmakers behind Black Journal begun to receive the recognition they deserve. Their work will be featured prominently in “Tell It Like It Is: Black Independents in New York, 1968 -1986,” a monumental series at the Film Society of Lincoln Center running through February 19 [2015].

Before the show even aired, though, there was resistance from the outside. In James Day’s The Vanishing Vision: The Inside Story of Public Television, former NET program director William Kobin remembers a tense meeting where plans for Black Journal were discussed with the heads of affiliate stations as one of the worst moments in his tenure. “The intensity of the stations’ opposition was totally unexpected,” he said, and a number of affiliates ultimately refused to air the show, citing a variety of unfounded concerns. Unwilling to back down, Day writes, “NET stood by its conviction that it was a black show, produced by a predominately black audience, and was better judged by those for whom it was intended.”

The premiere episode of Black Journal was well received by both the black and white press, with slight trepidation. The New York Times called it “one of the most exciting new television shows of the season,” even as it condescendingly praised the show as a “thoroughly professional piece of work,” while the New Journal and Guide, a historical African-American weekly newspaper based out of Norfolk, Virginia, celebrated its commitment to the black experience with the hope that, in the future, the show could be a space “where the situations of more ordinary blacks will be brought into focus.”

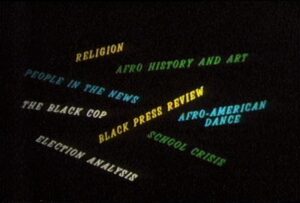

During its initial three episodes in the summer of 1968, Black Journal focused on a wide variety of subjects small and large affecting the black community, while adopting a rigid news-magazine format. The first episode featured segments on the recent struggle in Oakland, California between the Black Panthers and local police; Coretta Scott King speaking to the graduating class at Harvard; and a profile of New Breed, an all-black clothing design company, alongside a segment reviewing interesting and overlooked stories from the black press and a comedic sketch satirizing the mass media’s portrayal of African-Americans.

But there was a sense among the staff that the show wasn’t living up to its potential. “We confronted the management, because a lot of the producers felt they couldn’t present their own stories,” Hobson said. In August 1968, after only three episodes aired on television, 11 members of the Black Journal staff handed in their resignations as a sign of protest. “[NET] has deceived black people by advertising programs as being ‘by, for, and of black people,’ a statement to the press read. “This is not so. There is no black editorial control.”

“I think it took the management at NET by surprise a bit,” Kent Garrett, a member of the staff, recently said. “I remember we had a big meeting, and invited the press. Once that happened the management, as I recall, made the change.” The staff’s demands led to the ouster of Perlmutter, the white executive producer, who was moved to a consulting position. “I don’t think they resisted very adamantly,” Garrett recalled. “I think they knew we were really right, and it was false advertising.” Only nine of the 11 striking staff members returned to the show, with Hobson and researcher Sheila Smith taking positions at a similar show called Like It Is.

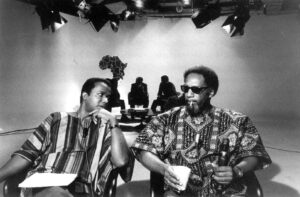

Taking Perlmutter’s place was William Greaves, a filmmaker with a long career already behind him when he arrived at Black Journal. Greaves, who already appeared on the show during its first three episodes as an occasional co-host, had started his career as an actor in New York, becoming a member of the famed Actor’s Studio and making sporadic appearances on Broadway. In 1952 he began working behind the camera, moving to Canada to produce documentaries with the National Film Board of Canada until 1963. In 1968, shortly before he joined Black Journal, he directed a documentary for NET called Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class, which in many ways would serve as a template for the kind of work the staff at Black Journal was hoping to produce.

“If you look at black filmmaking as an inverted pyramid, he’s the base that everything else comes from,” filmmaker and Black Journal staff member St. Clair Bourne said in an interview with the journal Black Camera in 2008.

In an earlier piece on the show’s history, written for the May 1988 issue of a magazine called The Independent, Bourne said that “Greaves believed each short documentary would be a teaching tool on how Black people could work to resolve common problems.” He added that Greaves “knew what we younger staff members didn’t: this filmmaking opportunity would not last, but the films would.”

The arrival of Greaves marked more than a symbolic change in the way Black Journal would continue. With his long background in documentary filmmaking, his presence served as an inspiration for the staff to expand outside of the format of the show, and to make work that not only spoke to a black audience but also had a personal connection to the people making it.

“First of all, Bill was an artist,” Madeline Anderson, a staff member on Black Journal said in a recent conversation. “He brought a sense of artistry to the way we made films. The young producers on the series were not afraid to experiment and Bill wasn’t afraid to let them. So some of the pieces weren’t really done in a newsreel style. They were done as little films.” Anderson began her career working with the legendary documentarian Richard Leacock, with whom she made her first film, Integration Report 1, and later became an editor. By the time she joined Black Journal she said, she had already worked in production houses with NET contracts for seven years. She began working on Black Journal as an editor and then, as the series progressed, Greaves began encouraging her to create her own pieces, where she would act as producer, director, writer, and editor, handling all responsibilities.

A Tribute to Malcolm X, a film Anderson made for the ninth episode of Black Journal, represents the freedom Greaves gave the staff to pursue their own personal projects. The film mixes various speeches given by Malcolm X, still photographs, and testimony from Betty Shabazz, Malcolm X’s wife, to present a multifaceted portrait of the complicated public figure. In later episodes of the series, Kent Garrett produced segments on African-American police officers and soldiers in Vietnam, and Greaves moderated a panel on the intersection of sports and politics with major black athletes including Jackie Robinson, Bill Russell, Arthur Ashe, and more. Under the leadership of Greaves, the segments became longer and more experimental, combining cinema verité documentary with direct address commentary and sequences that reflected the growing avant-garde cinema happening around the country. On the surface, Greaves and co-host Wali Sadiq began wearing dashikis and introducing the show with proclamations in Swahili, a more colorful presentation that reflected the depth and magnitude of black experience.

“What Bill inspired in us was that this was our golden age,” Anderson said. “This was the golden age for black input into the media, as film producers, directors, cameramen, and all of the aspects that go into making films.”

But as soon as Black Journal began to find its rhythm, arguably producing some of the most important documentaries of the period and reaching a far wider audience than ever before, there was pushback. Just a few months after Greaves became executive producer, the show faced several financial cuts, reported to be almost 80 percent of its total budget by the end of the first year. Over the final months of 1968 and into 1969, various reports from the New York Times indicated that the program received grants, first from Polaroid and later from Coca-Cola, that allowed it to continue for short periods of time.

Greaves would ultimately depart the show by the end of 1970 after only three seasons, leaving behind a legacy that he and much of his staff would continue through their work. Concurrently with the production of Black Journal, Greaves made Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One (1968), a landmark experimental film that has only been rediscovered in the last two decades, while St. Clair Bourne, Kent Garrett, Charles Hobson, and many others went on to distinguished careers within documentary film. Anderson left the show when Greaves left, and with his encouragement, she said, went on to make I Am Somebody (1969), an important feminist documentary about black female laborers on strike in South Carolina, before returning to public television as the first female African-American to produce a nationally broadcast television series.

Black Journal would continue, but in a much different form. Tony Brown, the former dean of communication at Howard University, took over responsibilities in 1970, which, according to Devorah Hunter in her study Black Power TV, represented a “profound aesthetic and political shift away from the experimental look of the episodes made under Greaves.” Brown, who would take the show in a progressively conservative direction that mirrored his own politics, would eventually slap his name on the front of the show, calling it Tony Brown’s Black Journal. Following continued declining resources, he would move the program to commercial television in 1977 for a short period of time before moving back to public television, where it still exists today.

The first three seasons, under the influence of Greaves and his remarkable staff, would have a profound effect on filmmakers for years to come. The critic Clyde Taylor, who has written extensively on the influence of Black Journal, claims the style of the show changed “the treatment of the editorial tone and the images of documentaries about black issues.” Because of their existence on public television, according to Taylor, the films made as part of Black Journal have been left out of histories of radical black filmmaking, but current historical work on the subject, with the help of programs highlighting the work of the various members of the Black Journal staff, have initiated a major revision.

But the biggest influence of Black Journal on succeeding filmmakers might just reside under the surface. “I think I took an energy from Black Journal with me throughout my career,” Kent Garrett said. “There was the idea of being on the side of the underdog, and having this feeling that you could really change the consciousness of people through film. That stuck with me. I felt that what we did on Black Journal did in fact raise people’s consciousness, and ultimately helped in the struggle and the arc of history.”

–Craig Hubert, “The Revolution Was Televised: On the Legacy of Black Journal”, Blouin Art Info, February 11, 2015